Why Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD) does not improve human rights outcomes

- Kate Robinson

- Mar 28, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 17, 2024

Image description: New Delhi

There has been a huge amount of progress in the development of international frameworks, standards and methodologies to support businesses in the management of social and environmental supply chain risks, over the last twenty years.

In this blog I’m going to focus on the prevalent methodology of the day, human rights due diligence. Why this methodology over others? First, due diligence is taking on mandatory form in a number of countries, from the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 to the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act and of course the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Second, over the last decade the number of companies talking about a due diligence approach has increased exponentially, stimulated by legal changes or otherwise – but everyone is doing it! Third, an entire support industry has sprung up to ensure companies have delivered against the process.

For these reasons and more, I’m keen to ensure that we stay alert to the realities of due diligence and question our assumptions on what it achieves for real people working in global supply chains.

What is human rights due diligence?

The approach been finessed since the launch of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights in 2011.

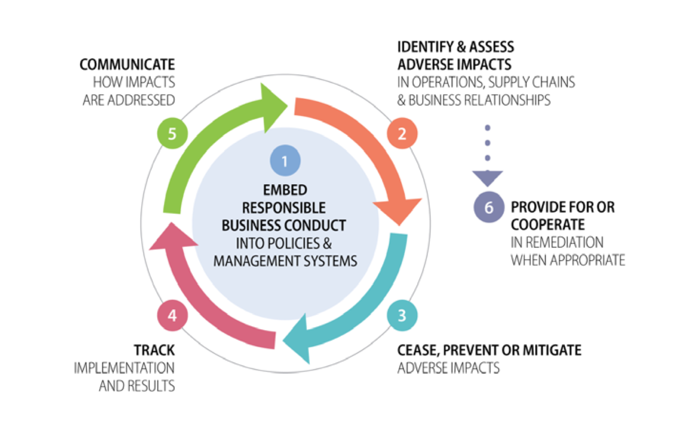

There are a number of frameworks to describe the process, which vary marginally with more or less detail given to different steps. The key ones are the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, ETI’s Due Diligence framework or the UNGP Reporting framework. I’m going to reference the OECD framework as it was developed through extensive consultation with member countries and is probably the most widely adopted.

Due diligence is really a simple management system, in OECD’s case consisting of six steps, which together would give a business an element of assurance that they have identified, managed and remediated on their material human rights risks effectively.

Source: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business, 2018. https://www.oecd.org/investment/due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-business-conduct.htm

So why doesn’t HRDD improve human rights outcomes?

1. Due diligence is not an improvement mechanism

This might seem like semantics, but it’s the obvious reason why human rights due diligence does not improve human rights outcomes. HRDD exists to assess risk, and mitigate harm when caused – it was never designed to be a process that would improve wages, reduce discrimination, or actively contribute to improve working conditions of people in global supply chains. It may result in fixing issues retrospectively, but it does not automatically lead to sustained improvements.

It is this core philosophy that enables risk management approaches such as social audit to continue, year after year, highlighting non compliances and closing them out, only for issues to reoccur time and time again. While there are examples of forward-thinking businesses that question the sustainability of this process, the vast majority do not.

And nor do they have to - yet. (Incoming legislation in Europe, Australia and the USA is set to change this, by requiring businesses to report on incremental improvements.)

But for now, lets stop assuming that human rights due diligence will improve human rights outcomes. Due diligence serves to map risks to business and highlight actions to minimise those risks. This is not the same as actively working towards improving human rights outcomes over time.

2. Companies focus on the easy bits

I know plenty of leading businesses that will rightfully take issue with this assertion, but for the most part, businesses focus on steps 1, 2 and 5 of the due diligence cycle. These are the steps we see in sustainability reports: the targets, the materiality assessments, the case studies. These steps require a person or team from HQ to oversee them, some level of budgetary sign off, and they produce a lot of good marketing fodder.

Steps 3, 4 and 6 are much, much harder. They require time and energy in the sourcing country itself, they are dependent on partnerships and collaboration, a good understanding of political context, regular liaison with civil society or government stakeholders, not least trade unions (heaven forbid!). Business systems here are nascent, not cheap, not easily scaleable, and perhaps just a bit too thorny. Is it any wonder that most companies steer clear unless they absolutely have to do otherwise?

3. The identification and assessment process is deeply flawed

This is a big topic, so I’ll try and stay concise. There are at least four significant reasons why corporate identification and assessment of human rights risks in supply chains is poor:

i. Weak methodology: The vast majority of businesses rely on some kind of site-level or desk-based assessment of their sourcing sites, but these assessments struggle to identify human rights risks which are either difficult to capture or difficult to measure.

ii. Lack of full supply chain visibility: The complexity of global supply chains makes it difficult for the end buyer/retailer to see their lower tiers (eg down to raw material), or connecting tiers (eg shipping), or their outsourced risks (eg informal homeworkers). Such opacity serves to keep attention on the lesser but visible human rights risks.

iii. Priorities driven by corporate strategy or focus areas: Most global companies undertake some level of national risk assessment but there aren’t many that go further to understand national development priorities or labour market policy, so that they can contextualise their efforts. Instead, we see priorities being set with an end consumer in mind, rather than what might drive sustainable change for workers in a given context.

iv. Worker and supplier needs do not direct the process: Running throughout all the above is the most critical point of all – without better ways of understanding the needs of workers and their employers in sourcing countries, along with the barriers faced by those in sourcing countries to improve labour conditions, corporate due diligence efforts can be disconnected and fail to improve outcomes for workers.

4. Prevention and remedy efforts tend to serve individual companies, not people

There is a zero sum problem when it comes to prevention activities – why should a buying company invest in skilling up a workforce or management cadre in a supplier site when that site supplies to all of its competitors which are not making the same investments?

The result of this is that a lot of prevention work either a) doesn’t happen or b) happens behind closed doors. Results aren’t shared, learning isn’t public. And while there are, fortunately, plenty of examples of collaborative initiatives in the prevention area (factory training programmes such as Better Work, or issue focused action (like that undertaken by the Ethical Trading Initiative), such collaborative prevention activities are the exception rather than the norm in global supply chains, and tend to be resourced and attended by the same big brands.

This is worse still when it comes to remedy. There are shamefully few collaborative efforts of grievance mechanisms at site level which would serve the needs of multiple buyers/retailers (Electronics Watch is a notable exception). Competition gets in the way, and it is the workers who suffer the consequences of being unable to access effective remedy.

5. Communication efforts report on outputs, rarely on outcomes, and never on long-term improvement

How can we track progress on human rights if no one is reporting on them? Open any CSR or sustainability report and you’ll see commitments and targets. There may be some reporting on indicators such as numbers of workers trained, or ratio women:men in the workforce. But these statistics tell us nothing. They are output measures at best and don’t give any indication of the action a business needs to take to improve workers’ lives. Moreover, they are rarely benchmarked for context or set against a timeline to demonstrate progress over time.

Another issue here is the inability to see across results. While efforts such as the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark are helping us to understand sector performance, it remains challenging to understand the net impact of global businesses in one particular production country. For this, we need to take a leap into national labour data which can be disconnected from sub-sector activity, patchy in its coverage and sporadic in its collection.

In conclusion, human rights due diligence, as practiced by many 1000s of global businesses, will not automatically lead to improved human rights outcomes for workers. For that to occur, we need to make some adjustments to the way these processes work, and elevate the voice of workers and national context in the process.

The Outcome Gap is working hard - with many others - on identifying workable solutions. This includes new methodologies, data sources, more transparency of results, sharing learning and much more.